Here in the Education section, we’ll be drilling deeper into our science and providing youth- and student-friendly project updates.

Contact the Education & Outreach Coordinator here.

Check out our resources page, which is always expanding.

Mascots on Ice

Our mascots are in Antarctica, having the adventure of a lifetime and helping conduct some cool science!

Follow their journey here and on our social media.

But our Adelie penguin and skua mascots still need names! Submit your suggestions here.

We want to know:

-

How much did the WAIS melt when Earth was warmer in the distant past?

-

How fast did the WAIS retreat (melt)?

-

What environmental conditions would cause the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to collapse in the past and into the future?

-

What would the local, regional, and global impacts be if the WAIS melted?

-

When in the future could it happen?

-

How will the WAIS react if we reach the Paris Agreement’s target of 2 degrees Celsius of warming? Is that target enough to save the Ross Ice Shelf and limit Antarctic Ice Sheet melt?

To answer these questions, we will drill through the ice and deep into the sediment below it in two places on the Ross Ice Shelf.

How much? How fast?

Why does it matter?

Antarctica is very far away, but what happens in Antarctica doesn’t stay in Antarctica. When land ice melts, that water enters the ocean and raises sea levels worldwide.

What happens when sea level rises?

- Did you know that hundreds of millions people around the world live at or close to sea level? Many major cities and important infrastructure such as power plants lie in coastal areas.

- Rising seas could displace many millions of people who live in low-lying coastal areas. That means that people and infrastructure will need to move farther inland. In turn, that will affect the people and communities (as well as other species) already living inland.

- But this sea level rise is not the same across the planet. As an ice sheet gets smaller, its gravitational pull weakens, causing water to flow away from it. With less ice pushing it down, Antarctica will slowly rise, too. (This is called glacial isostatic adjustment.) So, the greatest sea level rise will happen in the Northern Hemisphere, far from Antarctica.

The past is a guide to the future

The more we understand about Earth’s climate in the past and how the ice sheet behaved when it was warmer, the better we’ll know how it could react as our planet warms in the decades and centuries to come.

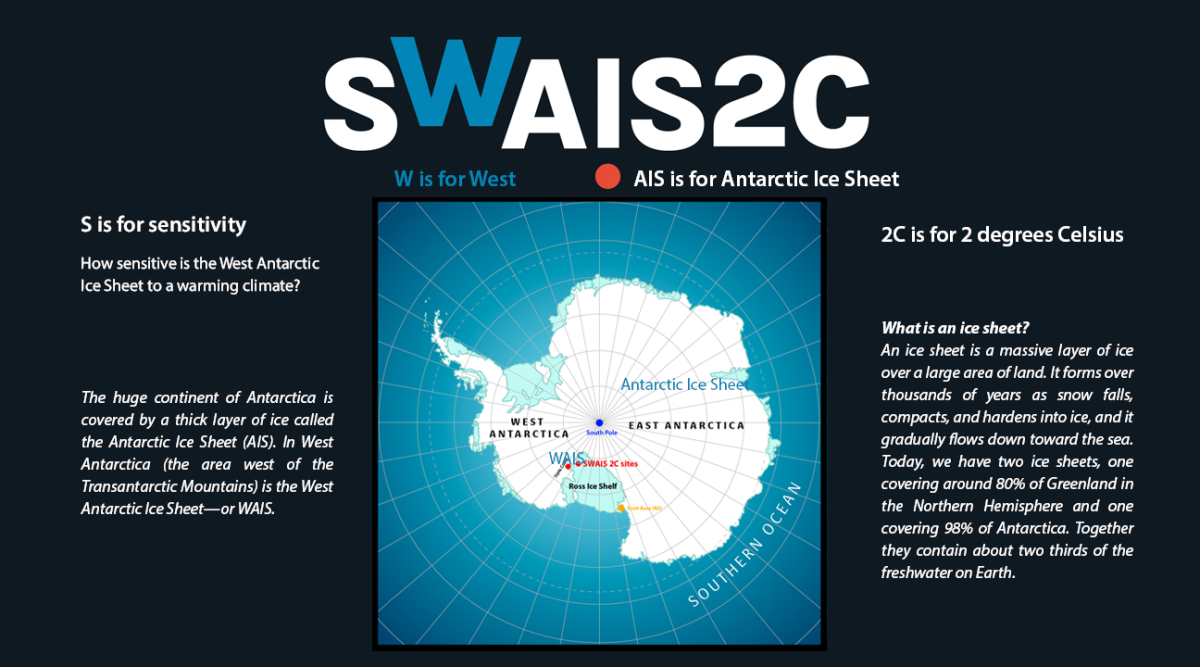

What is the Antarctic Ice Sheet?

The Antarctic Ice Sheet is up to 4.9 km (3 miles) thick, with an average thickness of 2.2 km (1.4 miles). That’s a lot of frozen water! If all Antarctica’s ice melted, sea levels would rise by about 57 metres (188 feet). If the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet melted, global sea level would rise by up to five metres (16 feet).

Who are we?

We are an international team of geologists, glaciologists, oceanographers, geophysicists, microbiologists, climate and ice sheet modelers, engineers, and outreach specialists. Many different international organizations are working together on this project, with more than 100 researchers from nine countries. And we are pioneers: no one has ever drilled deep into the Antarctic seabed at a location so far from a major base. No one has drilled into the sediment beneath the ice shelf so close to the center of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet!

What evidence are we looking for?

We are looking for evidence that the Ross Ice Shelf melted and that there were open seas far into the center of the WAIS, along the Siple Coast.

When marine organisms die, their remains sink and are incorporated into the sediment on the seafloor. Over time, layer upon layer of sediment is laid down, and these layers record changes in which species were living there and in environmental conditions over time.

Fossil hunters

We will examine the sediment deep beneath the ice shelf for microfossils (microscopic fossils) of diatoms (a kind of phytoplankton or photosynthetic algae). If we find microfossils of species that prefer warmer, sunlit, open waters, we will know the Ross Ice Shelf had melted when these diatoms were alive.

We will focus our study of the sediments on periods when Earth was warmer, to learn whether the Ross Ice Shelf disappeared and how much the WAIS melted.

But first, we need to get the sediment. A 700-meter-thick (2,300 feet) slab of floating ice sits between us and the fossils we’re hunting!

Scientific drilling

Scientific drilling is a technique for scientists to look far into Earth’s past by taking cores—long cylindrical samples of the sediment and rocks. Analyzing a core can include looking at its minerals, microfossils, magnetic qualities, and much more. This analysis can tell us what environmental conditions were present when the sediment was laid down.

Studying the cores

After the cores reach the ice shelf’s surface, our team will:

-

Do some initial analyses and x-ray them.

-

Carefully pack and store them to keep them pristine.

-

Fly them back to Scott Base then ship them to the Otago Repository for Core Analysis (ORCA) at Otago University in Dunedin, Aotearoa New Zealand.

-

Our international team of scientists will meet there to describe the cores, examine them, and take samples of the sediment for further analysis at their laboratories around the world.

-

Eventually, the cores will be stored at Oregon State University Marine and Geology Repository, USA

What will we do with the data?

Modeling

Numerical modelers are scientists who conduct experiments using data and computers. These experiments help them see various scenarios that could happen in the future.

Using SWAIS 2C data, our ice sheet and climate modelers will develop experiments to show us how the West Antarctic Ice Sheet behaved in the past. These will help us test the ice sheet and climate models we use to predict how much melting and sea level rise to expect. The result will be better and more accurate models to help us predict the future of the WAIS.

Working on ice

Our team and our equipment will travel over 1,000 km (620 miles) across the Ross Ice Shelf to the sites by over-ice tractor train traverse, and by air. We will drill through the Ross Ice Shelf and into the sediment below at two sites. Our team of scientists, engineers, and drillers will live in a tent camp at each site for up to three months. Antarctic field operations are scheduled to occur from November 2023 to February 2024 and November 2024 to February 2025. SWAIS 2C is a four-year project, so you’ll be able to see our progress over several years!